If you haven’t heard (touching too much grass?), Bun has been making some waves in JS-land with it’s big 1.0 announcement.

It’s been fun to watch the reactions.

Jessie Frazelle had a tweet that went tech-twitter viral, describing a feeling that many were thinking. How did such massive change come, seemingly, out of nowhere (relatively speaking of course; Bun was public about it’s work for the last year).

I’ve been thinking about it a lot, and tweeted a thread/diatribe about “The Innovator’s Dilemma” and how it applies to the current Bun vs. Node.js situation. And here’s the long-form version.

Innovator’s Dilemma Primer

“The Innovator’s Dilemma” is a book by economist Clayton Christensen in which he lays out his theory of “disruptive innovation”; one of the most impactful business ideas of the 21st century.

First, let’s talk about the alternative idea that the “disruptive innovation” theory opposes: “technology mudslide”.

In mudslide theory, a firm fails because it falls behind technologically in relation to other competing firms. The biggest risk a business can take is becoming complacent and not engaging in innovation which causes the mudslide into failure.

Reality - Like a ton of bricks

Seems simple. Too simple even. In fact, it’s naively simple and doesn’t model reality at all. In reality, most big firms (especially in the tech sector) never actually stop improving and even developing new innovations. Many of the hardware breakthroughs of the 60s-90s were first researched and developed by the very firms they later put out of business! They developed new tech, couldn’t figure out how to market it to their customers, abandoned it, and then got wrecked when a small competitor adopted and refined the tech into something huge and truly disruptive later on.

Let us speak the epic tale of Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) and all the insane shit they developed there, and try to explain why, in our tech-centric modern world, the CEO of Xerox isn’t God Emperor of Earth:

- Laser printers

- Ethernet as a local-area computer network

- Computer-generated bitmap graphics

- WYSIWYG modal text editors

- The graphical user interface, with skeuomorphic windows and icons, operated with a mouse

- Smalltalk, which counts as both Object-oriented programming (OOP) and integrated development environments (IDEs)

- Model–view–controller software architecture

- A resolution-independent graphical page-description language and the precursor to PostScript

How many of those became viable, long-term products or services for Xerox? If you guessed “almost none” you’d be right. Hell, if you didn’t already know about PARC, you would have no idea that Xerox, of all companies, was responsible for all those breakthroughs in the first place.

Let’s digress and just talk about Laser Printers for 1 minute. It makes sense that, of all things on that list, Xerox should have been able to capitalize on LASER PRINTERS, right? WRONG!

PARC invented the Laser Printer in 1971 but couldn’t successfully market it to it’s own customers because the existing analog photocopiers that Xerox already sold were more reliable, accurate, interoperable, and comparatively inexpensive. Instead, the first commercial laser printer was actually marketed in 1975 by IBM who sold it to data centers to serve as printers for mainframes. Eventually, Xerox brought it’s own Laser Printer to market to moderate success, but by 1984 it was Hewlett-Packard who launched the HP LaserJet that became the first mass-market laser printer.

Yes, It Applies to Modern Software Companies Too

But our modern, software-centric, world of delivering lightning over a series of glass tubes is sooooo different from 1970s-80s printer companies, yeah?

Gotcha.

Those of us who were there (millenial high-five), remember that Google never actually invented either Web Searching or Email, and yet their two most successfully adopted services to date are google.com and gmail: markets where Google beat out big established competitors. Google wasn’t the first to deploy those technological services, and they darn sure didn’t invent them, but they brought unique innovations to the ideas and improved on them drastically further than anyone expected, and proved you could build a mega-business on it.

Rinse and repeat this story for Amazon in online marketplaces, Facebook in social media, and Netflix in VOD. None of them invented the concepts, or were even the first in their spaces, though they certainly capitalized on “first mover advantage” in being early enough.

This happened repeatedly in products and services from the modern software giants, telecom infrastructure, automobiles, electronic memory, personal computers, and even hydraulic cranes.

But the lessons to be learned are from the competitors that were replaced.

- Yahoo.com, Momma.com, AskJeeves.com, Hotmail.com, MySpace.com, Friendster.com,

Recognizing the Pattern - Disruptive Innovation

Successful, outstanding companies had all the resources, technical know-how, timing, and positioning to capitalize on these trends, and were often involved in the early stages R&D of most of these innovations, but still failed to surf the righteous waves of disruption. By mudslide theory they were doing everything “right”, avoiding complacency, investing in technical innovations, and seeking out new markets; but they were still failing as unexpected competitors rise and took over the market.

“The Innovator’s Dilemma” as it has been understood

Ok, let’s get a little more concrete on the dilemma itself, as defined.

In “The Innovator’s Dilemma”, Christensen says that the reason that these big incumbents still get disrupted was because they faced a predicament between serving their customers and actually capitalizing on early-stage innovations.

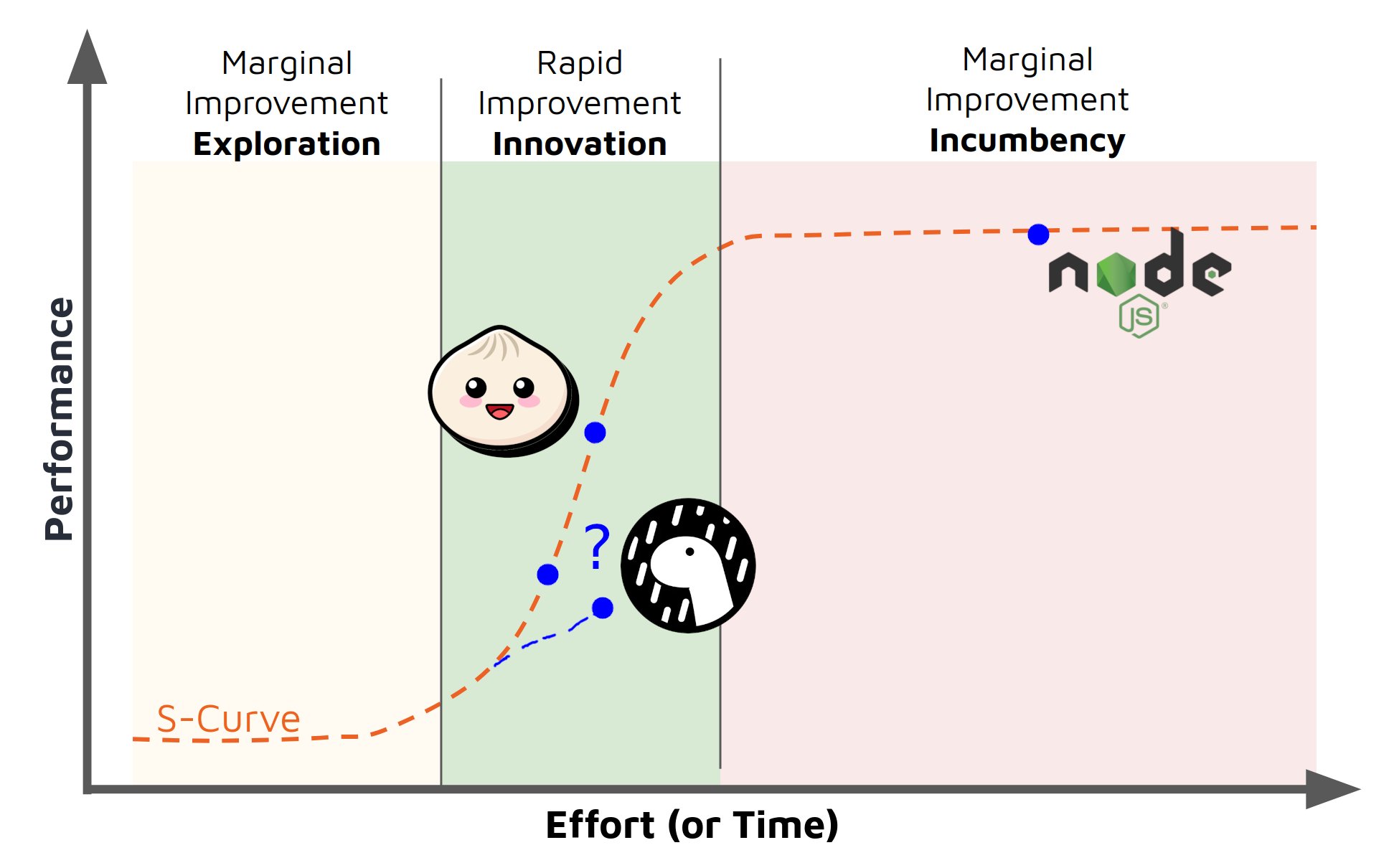

- Value to innovation is an S-curve

- Incumbent sized deals

S-curve, what?

Improving a product takes time and iterations, and it flows in 3 main phases,

which you can visualize graphically as an S, but you drew from the bottom to

the top; also you smoosh it sideways to look kinda janky. Yeah, that’s an

S-curve. sigh, Just look at the graphic below.

Phase 1 is the early iterations, where the curve is quite flat because each iteration provides minimal value to existing market (see Bun pre-1.0 announcements; interesting, maybe even exciting, but not enough to adopt; we’ve got real projects to deliver, after all).

But, innovations are buffs that stack, and over time, the value increases and

turns exponential. This is phase 2; the upward stroke of the S. Peak

innovation is now occuring, as well as peak value delivery. Mainstream

customers are now taking notice and wondering “where did this come from, and

where has it been all my life?”

What are the improvements happening in phase 2? It’s fixing all the things from phase 1 that made the product untenable for the larger market.

From what I’ve heard, Bun was segfault’ing something fierce only a few months ago, but everyone I’ve talked to has said that was resolved by 1.0 time. Good, because while early adopters might be ok with that in small pleasure-cruise leisure apps, obviously most Pro-senior-real-typescript-devs would never launch a big work app that way.

The wheel of time turns to phase 3, the most valuable improvements are completed and the peak value has been long delivered, and the curve levels out again where value per-iteration is small.

- Node.js has been in phase 3 for awhile now

- Bun is somewhere in phase 2

- Deno was in phase 2 and arguably still is, but who knows what’s going on with them, hence the apt

?label

Clear as mud? Good. Moving on.

Incumbent sized deals

First, does anyone dispute that big companies have big revenue requirements? No? Good, cuz that would be dumb.

Big company needs big dollarbucks to keep being … well … big. It’s a whole thing.

But where do you get those big dollarbucks? BIG DEALS BABY!!! Or at least from big volume of little deals. Either works; both are hard.

Big Deals === Big clients === Big expectations.

OR

Big Deal Volume === Big number clients === Big expectations.

Now before you get upset and yell at the screen “But the Node Foundation doesn’t SELL anything! It’s oPeN SOurCe!”

Broaden your mind. Deals && sales in this context isn’t money, it’s installs. It’s adoption. It’s the market of mindshare in the developer ecosystem. (Don’t worry, we’ll work a money angle in later)

The incumbent is always operating in the large market. This means they have the luxury of a huge customer set to amortize risk across. But this luxury is also a CURSE. With this huge customer set comes high expectations. These aren’t “soft” expectations either; leaving them unfulfilled may destroy your biz/product completely.

Matteo Collina does a great job explaining the very real expectations that Node.js is under: https://twitter.com/matteocollina/status/1700595301872976092

- Backwards compatibility

- Support tons of platforms

- Security

- Open governance; “everyone heard”

Question the validity of those expectations all you want, but they’re very real.

Bring it all together

Bun, the new entrant, is able to serve market niches that make no sense for the Node.js, the incumbent, to even consider addressing.

In this niche market are a bunch of customers who are fine with good enough:

- Lower stability guarantees (stable enough)

- Supporting fewer platforms (hit the key big ones; gtfo RISC chips)

- Running only a subset of existing packages from NPM (Does it run express and Next.js? eh, fine)

- Doesn’t check all the required boxes of the “open source foundation steering committee governance board” which is inevitably populated with either outright employees of FAANG/MAMAA or at least devs ok with currying favor with them (take VC money and flip the finger to “foundation donors”; the promised money angle)

Imagine Node.js, or any similarly mature large market product, announcing a new major version thusly:

“we’re less stable, drop support for X% of NPM packages, and only run on Linux and Mac, but we are Y% faster and added these cool quality of life features!”

The nuclear-take tweets (X’s?) would be flying before anyone even bothered looking at the features; and that wouldn’t be wrong.

Now, this may be obvious to you, my astute reader, but it has some sneaky implications:

The new entrant ALWAYS has more time to focus and innovate over an incumbent.

ALWAYS.

Incumbents still innovate and improve, just as NPM and Node.js have shipped good features and improvements over recent years, but those innovations are always limited to a certain acceptable space: an Overton Window of acceptable tradeoffs.

Yarn use to eat NPM’s lunch in install performance, until NPM adopted some similar tricks (lockfiles, flattened dirs, caches, blah blah). Now, NPM is competitive with Yarn and even beats it in some benchmarks I’ve seen.

Eventually, Node.js did, in fact, support ES Modules.

However… “The Innovator’s Dilemma” has told us that incumbents can still be innovative and fail.

Why?

Because the large market is RARELY interested in the early iteration of real groundbreaking innovations, but are HIGHLY interested in predictable improvements on existing product.

The niche and low-end market interests are inverted: high interest in innovation, low interest in methodical improvements. By definition, a niche, low-end market cannot be a significant source of customers for a large market incumbent.

The incumbent makes limited innovation for large market and still rakes in the usual success; all while the new entrant is DEEP in the highest value portion of the S-curve: innovating on the new product.

At some point, (like a benchmark dunking 1.0 release announcement that announced conquests of entire nations that didn’t even know they were at war), the new product becomes interesting to the large market (incumbent’s customers)

But, it is now too late for the incumbent to react! They are months or years behind the curve on the innovations as delivered and can’t match the new entrant’s rate of improvement, so the gap is WIDENING.

Wargame with me. Let’s say Node.js spends the next 3-6 months to copy most of Bun’s current features. Great success! But what’s Bun doing in that time? Obviously they’re moving further and will have have more tomorrow. And they have a high-performing team just hitting their stride in feature delivery. How likely do you think it is that this is Bun’s peak team performance?

This, really, is the essence of Clayton Christensen’s “Disruptive Innovation” theory. The incumbents can’t reasonable persue innovations that new entrants can because their market position is a limiting factor.

Conclusion

I’ll end with some rapid-fire bullet points:

- Disruption originates in low-end or niche mkts

- Current customers drive a firm’s roadmap

- Disruptive tech is fluid and impossible to predict the end result of it’s disruption

- Disruption is a process, not a product

- Innovations usually come from unmet needs on the fringes

- Success is not a requirement; you can disrupt the market but still fail as a biz/product

Also … Bun is sweet!

Fin